into the quarry

A Parallel Convergence

Vincent Castagnacci, Artist

Michael Gould, Sound Sculpture

ANN ARBOR, Mich.—When parallel paths happen to cross, innovation results. And so it was for two University of Michigan professors, one from art and the other from music, each traveling their own path until they met – a meeting that created a new genre they call a “visual/acoustic collaborative installation.” Nearly five years ago, following the suggestion of Bryan Rogers, Dean of U-M’s School of Art & Design, to “go out and have lunch with someone you don’t know to foster interdisciplinary links,” Vince Castagnacci chose Mike Gould as his dining partner.

Percussionist Michael Gould and visual artist Vincent Castagnacci knew that the combining of art and music was something that has been around for ages. But using the creative techniques and physical movements of the painter as the auditory theme of their collaboration generated something quite new. Adding the integration of digital audio technology and surround sound, this coming together of artist and musician formed a new synergy of art and music.

Recording Castagnacci’s actual act of drawing and painting through close-proximity microphone placement allowed Gould to use digital software to manipulate the results often stretching the time, lowering the pitch, sweeping a sound byte across an entire gallery and layering more bytes and musical ideas.

“Castagnacci uses a variety of implements to paint,” said Gould. He uses scrapers, snap-lines, electric sanders, rollers and wire brushes, creating an extraordinary and unique sound.”

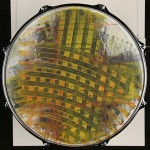

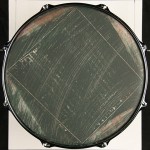

For this project Castagnacci painted on coated Mylar drumheads. Each completed drumhead, mounted on a 5-ply maple drum shell housing a speaker, acts as a resonator for the playback of the digitally altered “sounds of painting,” some of those sounds interpreted by Gould on drums.

“Mike Gould came to my work through the bias of his own means,” said Castagnacci. “Visually acute and musically gifted, he heard what he saw and recognized the source as familiar. Sonic attributes may or may not be contained or suggested in the surface look of my painting. These painted drumheads may embody and represent certain sound values. Whatever equivalent value resides in Mike’s music exists in the feeling for my work that his composition has managed to communicate.”

The convergence of these parallel paths has produced 24 paintings, each with its own speaker and separate channel of audio information, giving gallery patrons 22-channels of audio surround sound and two subwoofers. “These ‘sounding paintings’ will envelop the viewer/listener and create a truly unique experience and feel,” said Gould.

Audio Notes

Nearly five year’s ago in 2001; Vince Castagnacci sent me an intriguing e-mail message. The message contained the following:

He does in his discipline what I do in mine, namely applies various amounts of pressure to a surface using a variety of instrumental devices. He creates an aural arena structured in terms of rhythm and harmony corresponding to my visually textured one based upon the same principles. His interest in improvisation corresponds to my own desire to exercise equally the chance element and governed thought. He gives to color a sound and to sound a color. Finally, he is a generalist in his music making as I am in my art.

The message and subsequent years of conversations has sent us on a journey of creative exploration of both of our aesthetics and processes. Into the Quarry for me is taking ideas, concepts, and practical skills from each of our past creative endeavors and lives as thematic material for the present while simultaneously mining themes in common with one another. We have uncovered in this process a set of common themes that mesh both the visual and audio components into a hybrid-genre: a visual/acoustic installation. Vince has always surrounded himself with music and this can be seen in the variety of textures, themes, and rhythms in each of his paintings. My background is quite similar in respect to Vince’s. I have focused on music for much of my life but was raised in a family of artists that included painters, photographers, sculptors and lithographers. I have always been drawn to the visual element of the arts and this has always been key in the creation of my music, percussion playing, set-up and improvisations.

I have often found collaborations between a musician and a visual artist a very cursory interpretation of each other’s works; the musician plays what he or she sees and the painter paints what he or she hears. To go beyond this involves much more effort on the part of the collaborative team.

After a year of speaking with Vince about ideas of what we would like to see from our collaboration and our own interests in individual creativity, I asked for a catalog of some of his work and to see his studio. I also gave Vince a recording of some of my playing and compositions. What was most striking at that time was Vince’s use of texture, which would be akin to my use of timbre. Initially, when I looked closely at his paintings, I wanted to hear the sound of the implement being scraped across the canvas. The sharp lines being carved into the paint. I wondered if Vince ever heard himself paint. I decided at that point that the sound of Vince painting would become the central auditory theme of the project. After watching and listening to Vince paint, I derived four thematic motifs or principal themes:

T1 RollerT2 SnapT3 ScrapeT4 Stirring

There are also a variety of hybrid sounds Th1-4. For example, the string of the snap line being stretched or placed on the painting surface or the drum head bouncing off of the easel from the roller. In other cases, a theme may be electronically manipulated using a variety of software samplers and effects Te1-4. This method of manipulation becomes important in the transfiguration of themes and subsequent variations. The use of percussion also plays an important supportive role with the four principal themes. I have used tuned percussion such as gongs and crotales (tuned cymbals) to accentuate key harmonic or poly harmonic points. At other times, percussion plays an accompanying role to the themes to propel time forward P. The intertwining of Vince painting along with my percussion playing at times becomes indistinguishable from one another. I imitate and initiate both theme and accompaniment. The duet forms a composite rich in texture and rhythmic complexity. This has been a unique challenge for me and in the end very rewarding.

In most cases, each of the paintings contains at least two of these principal themes. From a musical point of view, one can see (hear) the rich textures (timbres) and interwoven layers (harmonies) flowing through each painting; a scrape of one color unveiling a second that is pierced by a snap line. I would consider two or more simultaneous painting actions such as described above as harmonic motion (in a suspended state). In most paintings, the harmonic motion is so dense that it becomes poly harmonic: the sounding of more than one harmonic concept. This is often reflected by the simultaneous use of multiple auditory themes.

After careful study of each other’s work and extensive dialogue on each of our aesthetic, processes and our individual past’s we left each other alone in our respective studio’s with the confidence that what we were doing on our own would be synthesized into a cohesive union. Doing so helped create the idea of the parallel metaphor. We would come back for a glimpse and a conversation with the excitement that what we were doing was at some point going to converge. Over the past five years we have become a close collaborative team and friends.

I. The Painter Alone

II. The Musician Alone (direct interpretation)

The musician having studied the artist’s sounds begins to emulate them just as he would any musician he respects. Having practiced these sounds, the snap, scrape, stir and the roller he reverse-engineers a finished painting and uses it as a score for time and texture. When asked, the painter could not identify if it was he who was painting or the musician emulating him paint.

III. Interlude I, The Quarry Past and Present

The dripping of water defines a new space and hints at the musician’s past. The melody is played on the crotales and is accompanied by the hands of the painter scraping across the canvas T3. Accompanying the crotales and hand scrape is the low beating of the canvas bouncing off of the easel. These interludes serve to introduce and reinforce key thematic material mixed with various ìminedî sound bites from the musicians past.

IV. Roller/Snap/Scrape Theme

The introduction states a simplistic theme T1 in its simplest light. A roller resonates from one channel. This is immediately followed by a fully orchestrated treatment of the roller theme and the introduction of the snap line T2. An interlude follows using a tuned flexible pipe Pta. This sample has been electronically manipulated and stacked to provide harmonic rhythm and momentum to the next section Ptae. A conversation between the two artists (2001) begins and is subsequently treated as a canon. The movement ends with the sound of (ìone thingî) a flywheel from a truck Pti (ìrightî).

MG: ìIt’s a performance,

VC: It’s mutually significant,

MG: yeah, yeah, yeah

VC: I mean you know, like, like, Painting is not about time,

MG: right,

VC: it’s about space.

MG: yeah

VC: Music is not about space, it’s about time BUT there is space in music

MG: you need it, yes

VC: and there is time in painting.

MG: absolutely

VC: Now, if, if it can become, I mean, if, if, if, if, they share that potential to exist in either, you know,

MG: right

VC: zone, suppose that, that whole thing disappears and it becomes one thing.

MG: right.î

V. Interlude II, The Quarry Past and Present

Michael Chikuzen Gould, Shakuhachi

The presence of an electronically manipulated roller Te1 consumes the low-end of the audio spectrum while a more active crotale melody flows above it. These are akin to highly contrasting colors helping set one another off and fool the eye (ear). There is a shakuhachi (Japanese bamboo flute) that enters softly (mono, channel 1) performed by my namesake, Michael ìChikuzenî Gould. Accompanying the flute are tuned gongs, wind chimes and water. One may move very close to the painting and see more or see less as one may move quickly hearing a composite of sound or nothing at all. Quiet your mind.

VI. To an Old Philosopher in Rome, Wallace Stevens Speaks

Early on in our collaboration, Vince wanted me to read some of Wallace Stevens poetry. I would often see him at our local coffee haunt reading his tattered copy that contained dozens of ìstickyî notes and dog-eared pages. Since it is out of print, I found a copy at a used bookstore online and better yet, found a recording of the poet delivering the poem To an Old Philosopher in Rome. Accompanying him is a typewriter from the 1950′s. I sampled various keystrokes including the space bar, return and the bell and literally played along with him speaking. I think of this section as the poet alone in his room (studio) with his thoughts coming alive through the typewriter. These sounds are complimented by one another with a ìwetî or reverberant sound of his voice and the ìdryî or secco sound of the typewriter. Underneath these two sounds is a loop of Vince scraping on a canvas with a wire brush (in 10.2 surround). It has been detuned and thus gives it a very low and slow drone-like quality Te3.

To an Old Philosopher in Rome, Wallace Stevens (1952)

(excerpt)

On the threshold of heaven, the figures in the street Become the figures of heaven, the majestic movement Of men growing small in the distances of space, Singing, with smaller and still smaller sound, Unintelligible absolution and an end –

The threshold, Rome, and that more merciful Rome Beyond, the two alike in the make of the mind. It is as if in a human dignity Two parallels become one, a perspective, of which Men are part both in the inch and in the mile.

How easily the blown banners change to wings. Things dark on the horizons of perception Become accompaniments of fortune, but Of the fortune of the spirit, beyond the eye, Not of its sphere, and yet not far beyond,

The human end in the spirit’s greatest reach, The extreme of the known in the presence of the extreme Of the unknown. The newsboys’ muttering Becomes another murmuring; the smell Of medicine, a fragrantness not to be spoiled…

The bed, the books, the chair, the moving nuns, The candle as it evades the sight, these are The sources of happiness in the shape of Rome, A shape within the ancient circles of shapes, And these beneath the shadow of a shape

In a confusion on bed and books, a portent On the chair, a moving transparence on the nuns, A light on the candle tearing against the wick To join a hovering excellence, to escape From fire and be part only of that which

Fire is the symbol: the celestial possible. Speak to your pillow as if it was yourselfÖÖ.

VII. The Poet Continues in Rome and the Painter Paints

This movement continues where the last left off. Wallace Stevens continues to read his poem, To an Old Philosopher in Rome. The painter and percussionist abruptly interrupt him. Bits and pieces of an electric sander represent the painter while the percussionist bows a cymbal. Underneath the sander and cymbal is the sound of a piano without any attack. At a certain point, frustrated, the poet’s thoughts are now the typewriter and his poem only reflex. The piece continues in retrograde, the poet speaking backwards.

To an Old Philosopher in Rome (continued)

Be orator but with an accurate tongue And without eloquence, O, half-asleep, Of the pity that is the memorial of this room,

So that we feel, in this illumined large, The veritable small, so that each of us (MUSIC) Beholds himself in you, and hears his voice In yours, master and commiserable man, Intent on your particles of nether-do,

Your dozing in the depths of wakefulness, In the warmth of your bed, at the edge of your chair, alive Yet living in two world, impenitent As to one, and, as to one, most penitent, Impatient for the grandeur that you need (Retrograde)

VIII. Interlude III, The Quarry Past and Present

Michael Chikuzen Gould, Shakuhachi

Dripping water enters along with the sound of a bowed cymbal. The painter’s incessant stirring follows the introduction but has been detuned, filtered and looped Te4. The shakuhachi enters and is featured prominently in contrast to the other interludes. The crotales enter with a new melody along with a gong.

IX. 3:2 Cup Attack

Following the premise of Interlude III, the motif of stirring paint is expanded and featured in this movement T4. The first instance of stirring begins approximately 14 seconds from the beginning and is heard as a polyrhythm of 3 against 2 (3:2 or a simple polyrhythm is the simultaneous sounding of two or more independent rhythms taking the same amount of time). The beginning of each grouping of 3:2 is heard by the closing of a paint can. Other entrances of stirring occur against the 3:2 motif forming a complex rhythmic structure both within and outside of the established meter and tempo resulting in polytempo. The jumping of both meter and tempo form a cacophony of sound similar to phasing heard in minimalist music.

X. 4:3 Cup Attack Postlude

“Music is not about time it’s about space.” Although the piece begins as a reprieve of 3:2, it transforms to 4:3. It ends with the musician’s obsession with time and time phasing.

XI. The Painter Alone (finishing version 1)

With ì360 degreesî of possible angles to paint with or to form sound around, the artist is alone in his studio finishing the first version of a painting. This is a short reprise to bring the listener/viewer back to where we came from and prepare for the next movement.

XI. The Painter Alone (finishing version 1)

With 360 degrees of possible angles to paint with or to form sound around, the artist is alone in his studio finishing the first version of a painting. This is a short reprise to bring the listener/viewer back to where we came from and prepare for the next movement.

XII. The Musician Alone (Improvisations based on 4 themes)

Jason Corey, Engineer

After studying all of the sounds of the painter and creating much of the music for the collaboration, sitting behind the drums was the fastest way to synthesize all of this material into a short multi-movement solo and to show the direct transformation from the painter to the musician. The sounds of the painter both acoustically and electronically were in my head while I performed this live in the recording studio. I did the entire movement in one take and completely improvised the entire passage. At the time, I did not think at all about form or that this would become a movement in the collaboration-I just let myself play.

4 sections

Roller with altered/unaltered scrape sounds and the snap line on the snare drum and tom-tom.

Altered scrape sounds-acoustic treatment of an electronic sound.

Canvas Bounce-the sound of the canvas bouncing off of the easel as a motif.

Stirring-the sound of stirring and most of the themes treated more skillfully.

Vincent Castagnacci

Vincent Casagnacci is a painter with studios in Pinckney, Michigan and Gloucester, Mass. From 1959 to 1962 he studied drawing, painting, printmaking at the Boston Museum School and drawing and sculpture with George Demetrios in Boston and Gloucester, Mass. The Museum School degree program with Tufts University awarded him a BS Ed in 1963. In 1964 he received a BFA from Yale University and in 1966 from Yale an MFA. Occasional studies were pursued with Professor Alfredo Barilli in Rome.

While at Yale Castagnacci was an instructor in Basic Design at Southern Connecticut State College. From 1966 to 1973 he was an associate professor at Old Dominion University. He came to the University of Michigan in 1973 where he is currently professor of art.

Castagnacci has received numerous grants and fellowships from Michigan and most recently was a Mellon Scholar at Kalamazoo College. In 1980 he was awarded a Citation and Grant from the American Academy in Rome where he was visiting artist for nine months. In 1999 he was named Arthur F. Thurnau Distinguished Professor of Fine Arts. He has lectured and published consistently in this country, in Rome at LíIstituto Nazionale per la Grafica and at the Gebaudelehre, Technische Universitat in Vienna.

Castagnacci has exhibited in numerous solo and group exhibitions both here and abroad. In 1996 hope College mounted a retrospective exhibit ìCASTAGNACCI; Works 1968-1995î which is documented in an extensive catalogue. Castagnacciís abstract work in painting, printmaking and drawing has been centered in the principle of variational development. His work articulates a personal geometry and communicates a strong sense for tectonic values. A five-year collaboration with percussionist and composer Michael Gould has most recently culminated with ìInto the Quarryî: an installation celebrating the convergence of art and music in space and time.